Laura Knight: A Singular Vision

"There was beauty in very simple things if one had eyes to see it."

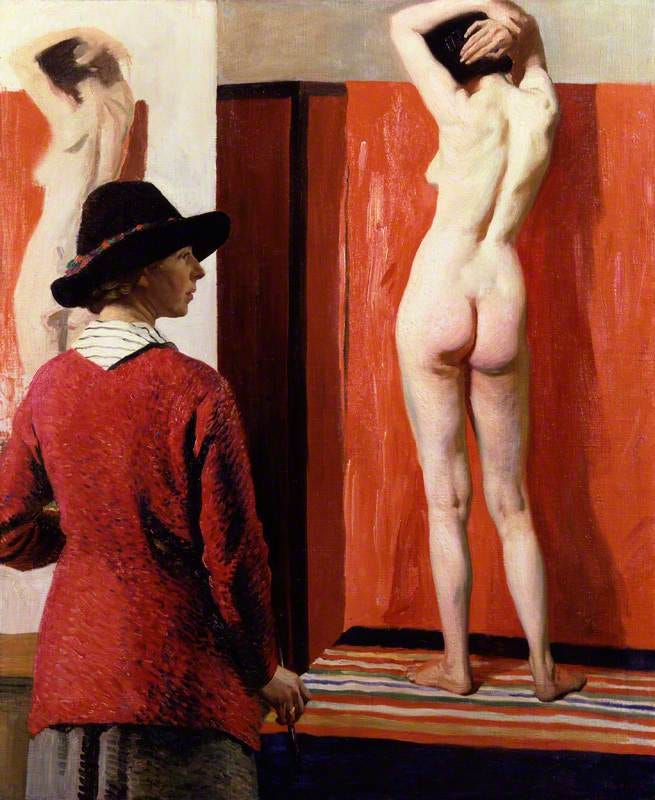

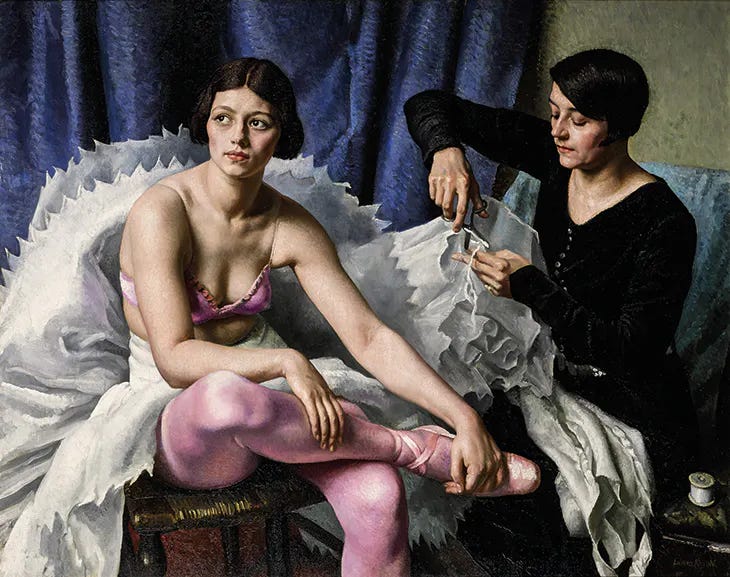

Dame Laura Knight DBE RA RWS was one of the most popular artists of the twentieth century and enjoyed a career that spanned eighty years. She was the first female artist to be elected to the Royal Academy, and to be made a Dame of the British Empire. Famous for her colourful portrayals of life in Britain, she was particularly celebrated for her stunning portraits of young women, ballet dancers and circus performers.

Laura Knight was born Laura Johnson in Long Eaton, Derbyshire, on 4th August 1877. She was the youngest of three daughters born to Charles Johnson, listed on the marriage certificate as a lace draper, and his wife Charlotte Bates, an art teacher. Her parents’ marriage was not a happy one - Charles mistakenly believed he had married into a wealthy family and, when Laura was just a few months old, the marriage ended.

In 1879, she and her two elder sisters, Charlotte and Evangeline, moved with their mother to their grandmother’s home in Nottingham. Life was financially difficult for the family and Charlotte (senior) supported them by offering private art lessons for local middle-class families. She also encouraged her daughters’ love of art and Laura’s enthusiasm and talent were recognised at an early age.

One of the greatest moments of Mother's life came when she found that I, a mere baby, was never so content as with pencil and paper; even before I could speak or walk, I drew. There was no question of my purpose in life.

In 1889, at just twelve years of age, Laura was invited to live with a relative in France, to attend school there and eventually study art in Paris. Sadly, the death of her sister Evangeline ‘Nell’, the poor health of her grandmother, and family bankruptcy meant the trip was cut short, and she returned to England.

Exempted from traditional school, Laura was instead offered a scholarship to attend Nottingham School of Art, and enrolled there in 1890. Classes began in the mornings at 9.30 with a long break in the afternoon and evening classes from 6.30-9.30 pm. She studied there until 1894, but in 1892 when her mother died from cancer Laura, aged only fifteen, was left responsible for her mother’s private art classes and supporting the family - alongside her studies.

It was at the Nottingham School of Art that she met and became friends with fellow artist Harold Knight and, after they graduated, they moved to Staithes - a small Yorkshire fishing village, just north of Whitby, that was home to a small colony of artists. Laura was inspired to paint the villagers and fishermen there and, again, supported herself financially by giving art lessons, this time to visiting students.

It was there that I found my own way of seeing and trying to speak of it in pencil and colour, instead of copying other people, particularly Harold.1

Laura and Harold initially lived in Staithes as companions. Though she had suggested marriage, Harold was concerned about their lack of financial security. But, in 1903, one of Laura’s paintings, Mother and Child, was accepted for exhibition at the Royal Academy and subsequently sold for 20 pounds. Later that year, seven years after they arrived in Staithes, twenty-six-year-old Laura Johnson, and twenty-nine-year-old Harold Knight were married.

Though Laura was grateful for the creative opportunities at Staithes, she and Harold struggled with the savageness of life there, the destructiveness of the weather, and the regular loss of life in the fishing community. In 1907, though initially reluctant, Laura agreed with Harold that it was time to leave and they moved south to Newlyn in Cornwall.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century Newlyn, like Staithes, was also home to an artistic community with artists attracted to the area's landscape and natural light. The Opie Memorial Art Gallery opened there in 1895 and artist Stanhope Forbes founded the Newlyn School of Art in 1899. When Laura and Harold arrived, among the many artists living and working there were Walter Langley, Harold Harvey and Thomas Cooper Gotch. Dod and Ernest Procter also moved to the area shortly after.

As they settled in the village, Harold focused on portraiture and Laura developed the colourful palette she became known for, concentrating on portraits of villagers and tourists against the beautiful backdrop of the Cornish landscape and coastline.

While Harold was generally reserved in company, Laura enjoyed the artists’ many social activities that included outside parties and skinny dipping. Sadly, their happy life in Cornwall was cut short in 1914 when war broke out. Harold, a conscientious objector, was forced to work as an agricultural labourer, and Laura’s beloved Cornish coastline was placed under military restrictions.

When the war ended in 1918, they left Cornwall and headed to London. Laura adopted an eccentric artistic personal style - wearing bright colours, hats and sometimes cloaks - and became interested in painting the informal backstage lives of ballet dancers and circus performers. As she made friends with influential figures, such as theatrical mogul Sir Barry Jackson, leading ballerina Lydia Lopokova and circus owner Bertram Mills, she was offered increased access to dancers, performers and their dressing rooms. In 1930, she also toured across England with one circus company.

Who among the audience could imagine their matchless ballerina hanging on to a curtain in the wings, panting, almost too tired to stand, with a stream of sweat pouring down her neck?

[Bertram Mills] gave her permission to go where she liked during rehearsals, and soon she was producing studies of trapeze artists, acrobats, tumblers, jugglers, contortionists, as well as dwarfs, clowns, and the circus animals. She painted a huge canvas, Charivari, which brought in nearly everyone in circus life; it was exhibited at the Royal Academy summer exhibition in 1929 and was caricatured in Punch, with politicians portrayed as the various circus performers.2

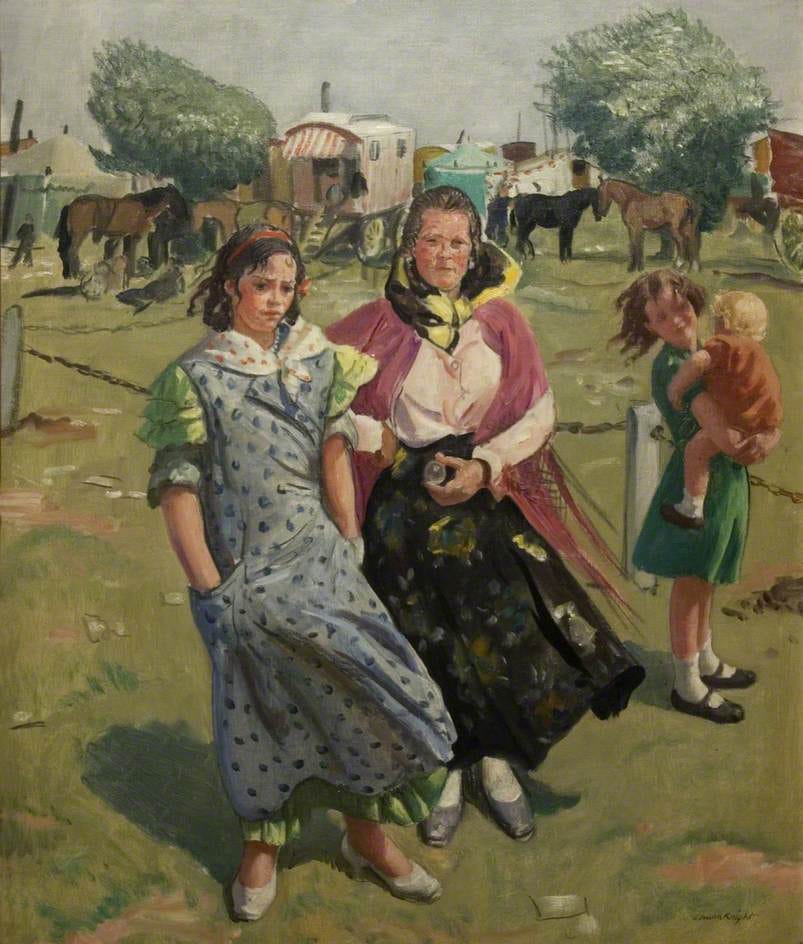

In the 1930s, Laura also visited horse-racing courses and painted racing scenes and the Roma Gypsies she met there. In 1935, she was only the second female to be elected to full membership of the Royal Academy and also began writing an autobiography, Oil Paint and Grease Paint, that was published the following year.

He will be a dull reader who does not feel … that he has not only followed the varying fortunes of a remarkable artist but has also watched the development and unfolding of a great personality.

Review in the Manchester Guardian

During the Second World War, and in her sixties, Laura was an official war artist, working in some physically difficult conditions. Her most famous work from that time, Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech-Ring depicted a female munitions worker operating machinery in the Royal Ordnance Factory in Newport.

She was also assigned to paint the war crimes trials at Nuremberg after writing to the Secretary of the War Artists’ Advisory Committee.

[It would be] a pity for such an event to go unrecorded, and I feel that artistically it should prove exciting.

In the years following the war, Laura continued to paint, in particular, the countryside around their home in Worcestershire but, sadly, her work was not fetching the high prices it once did. As both she and Harold’s health began to deteriorate they moved to Colwall in Herefordshire where Harold died on 3rd October 1961.

She published her second autobiography The Magic of a Line in 1965 and the same year the Royal Academy exhibited 250 of her paintings.

In 1970, the Castle Museum in Nottingham also opened a Dame Laura Knight exhibition on 8th July. Sadly, Laura would not be in attendance, passing away on the 7th of July, aged ninety-three.

There was beauty in very simple things if one had eyes to see it.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this biography, please like and/or share. And, as always, I would love to know your thoughts in the comments. If you wish, you can also Become a Member and/or read the suggested Beyond Bloomsbury posts below. Until next time…

Images:

Images on Beyond Bloomsbury are usually credited. I conduct thorough picture research, but please let me know if you believe a credit needs to be added or corrected. Thank you!

Sources and Recommended Reading:

Dunbar, Janet. Laura Knight. 1971.

Fox, Caroline. Dame Laura Knight. 1988.

Knight, Dame Laura. Oil Paint and Grease Paint. 1936.

Knight, Dame Laura. The Magic of a Line. 1965.

Morden, Barbara C. Laura Knight: A Life. 2014.

Morden, Barbara C. Laura Knight: A Life. 2014. 87.

Dunbar, Janet. Laura Knight. 1971.

What an interesting and inspiring woman - this was such a great read. Love her painting style too, so beautiful. "There was beauty in very simple things if one had eyes to see it." - Words to live by!

Great synopsis of that wonderful artist Dame Laura Knight. I read her autobiography many years ago and was so impressed with her dedication to her art and the way she and Harold overcame abject poverty to create their paintings. Great dedication and talent combined.