Sir Stanley Spencer is considered one of the greatest English artists of the twentieth century. He is known mainly for his Biblical scenes that depict his beloved home village, its residents, and his profound Christian faith.

Stanley was born on the 30th of June 1891 in Cookham, a small Berkshire village thirty miles from London. He was the eighth surviving child of musician William Spencer and former choral soprano Anna Caroline Slack, with seven brothers and two sisters. Sadly, a set of twins died in infancy.

The Spencers were Methodist and lived in a house called Fernlea on Cookham High Street, one-half of a semi-detached villa built by Stanley's grandfather, Julius. His uncle's family lived in the adjoining property.

Stanley is said to have had a happy childhood and has recounted memories of feeling safe and loved. His two elder sisters, Annie and Florence, taught him at home, and though he was not intellectually confident, his artistic talent was recognised from an early age.

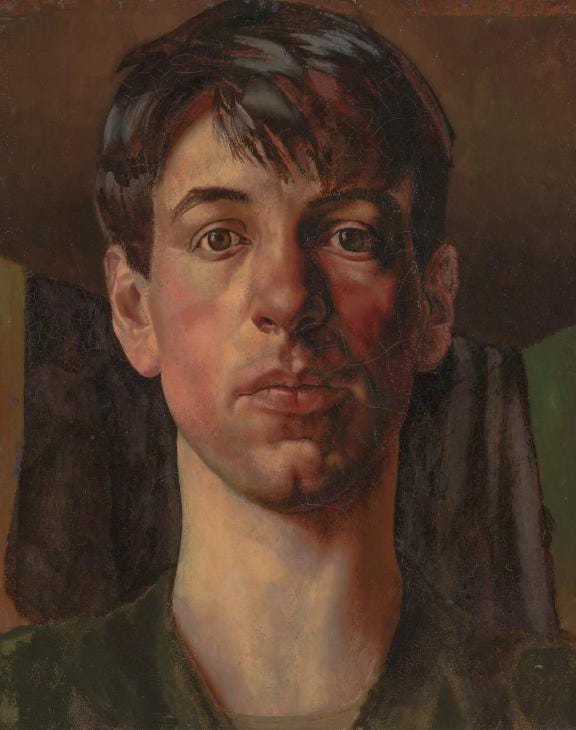

His first formal art training was with a local artist, Dorothy Bailey. In 1907, he enrolled at Maidenhead Technical Institute before transferring to the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art in London the following year.

Founded as part of University College, London, in 1871, the Slade had two particularly golden eras - the first was at the end of the nineteenth century with students including Gwen and Augustus John, William Orpen and Percy Wyndham Lewis. The second was while Stanley was there, studying alongside notable contemporaries such as Dora Carrington, Christopher Nevinson, Mark Gertler and Paul Nash.

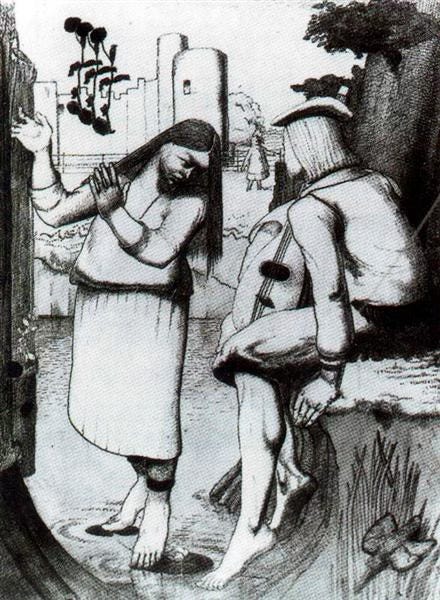

The four years Stanley spent at the Slade were not always happy, though; he was different from many of his fellow students and often the victim of practical jokes. But he was also nicknamed Our Genius and produced paintings such as The Fairy on the Waterlily Leaf (1910) and The Nativity (1912). Gwen Darwin, granddaughter of Charles Darwin and six years his senior, also befriended him and became his confidante and protector.

After graduating from the Slade in 1912, he worked prolifically for three years. Painting with an intense vision, he referred to that time as his Golden Age.

When I left the Slade and went back to Cookham, I entered a kind of earthly paradise. Everything seemed fresh and to belong to the morning.1

But this Golden Age would not last.

Here we part with the year 1913 which has had many joys for me and few sorrows. What has 1914 got locked up in its bosom for me and mine? We shall see in time.2

On Tuesday, the 4th of August 1914, Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith announced a final warning to Germany demanding the withdrawal of its troops from Belgium. There was no response.

Though First World War enlistment was voluntary, Stanley wanted to join the Royal Berkshires as an infantryman. But, dissuaded by his mother, concerned about his fitness (he was just 5ft 2" and weighed less than seven stone), he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps instead - working as an orderly at the Beaufort War Hospital in Bristol. On the 7th of December 1915, he wrote to his friend, the artist Henry Lamb:

Two hundred patients or more would arrive in the middle of the night - this was disquieting and disturbing. One had just got used to the patients one had; had mentally and imaginatively visualized them. I have to move patients with their beds from one ward to another or perhaps to the theatre.

On the 23rd of August 1916, he left Bristol for Macedonia as part of the 68th Field Ambulance Unit. Twelve months later, he joined the 7th Battalion of the Royal Berkshires, fighting on the front line. Stanley remained at the front line for more than two years before being invalided out after contracting malaria.

He arrived back in England on the 12th of December 1918 and travelled directly to Cookham, where he belatedly learned about the death of his elder brother Sydney on the 24th of September. The loss of his brother and so many of his comrades had a lasting effect on him and affected his work for the rest of his life.

In 1919, commissioned by the British War Memorials Committee of the Ministry of Information for a proposed Hall of Remembrance, he painted Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916.

Later that year, and feeling restless with life at Fernlea, Stanley left Cookham for the neighbouring village of Bourne End, where he lived with trade union lawyer Henry Slesser and his wife, Margaret. The Slessers were a religious couple and commissioned three paintings from him for their private chapel. He lived with them until 1921 before staying with artist Muirhead Bone in Hampshire, followed by a summer with his friend Henry Lamb in 1923.

In October of 1923, he moved to Hampstead, rented a studio from Lamb, and joined the New English Art Club. There he met Sydney and Richard Carline and their sister Hilda, a Slade alumni. Hilda was talented and beautiful, and Stanley was captivated by her.

I used to love passing the open door of her bedroom and see her changing some stockings, and just for a moment her pearly leg, and she loved to show as much leg as possible.3

With his feelings reciprocated, Stanley proposed to Hilda, and they married in 1925. Around this time, he also began work on The Resurrection, Cookham - a large painting that depicted his friends and family in the graveyard of the village's Holy Trinity Church - watched by God, Christ and other religious figures. It was exhibited at the Coupil Gallery in 1927 and described by a Times critic as "the most important picture painted by any English artist in the present century…"

At the end of the First World War, a Louis and Mary Behrend had contacted Stanley and commissioned him to produce a collection of paintings in memory of Captain Henry Willoughby Sandham, Mary’s brother, who had died in action.

The paintings were to be exhibited in a gallery the couple were building in the village of Burghclere, Berkshire. But, Stanley requested the building be built in the style of a chapel. The project took five years, and he completed sixteen paintings, including Bedmaking, Washing Lockers and Sorting the Laundry. The collection, rather than portraying horror or heroism, showed the everyday and sometimes mundane aspects of life at war.

In 1932, Stanley returned to Cookham with Hilda and their daughters. They moved into Lindworth, a semi-detached villa in the centre of the village with a large garden and space to build a studio.

Sadly, by now in his early forties, he was feeling dissatisfied and restless in his marriage and, as a celebrity, was receiving attention from other women. In particular, he had caught the eye of artist Patricia Preece, who lived nearby with her sexual partner Dorothy Hepworth. Preece modelled for him for the first time in 1933 and accompanied him on the first of two painting trips to Switzerland.

After the second trip, a humiliated Hilda moved to Hampstead and began divorce proceedings. In May 1937, with the divorce finalised, Stanley and Preece were married. But Preece invited her partner Dorothy Hepworth to Cornwall on their honeymoon and slept in her room. When she and Stanley returned to Cookham, Preece continued to live with Hepworth, and historians suggest she and Stanley never consummated their marriage.

When the relationship came to its inevitable end, Preece refused to grant Stanley a divorce. And, as he had signed Lindworth over to her, he had to leave his home. He also left Cookham, moving into a bedsit at Swiss Cottage, Hampstead, before staying with friends and artists George and Daphne Charlton at Leonard Stanley, Gloucestershire. Hoping to be reconciled with Hilda, he painted pictures of his first marriage, corresponded with her, and visited her often.

In 1939, at the outbreak of the Second World War, the War Artists’ Advisory Committee commissioned him to paint the daily activities of workers at Lithgow’s Shipyard at Port Glasgow. By the time the war ended in 1945, he had completed eight paintings for the Imperial War Museum.

Stanley returned to Cookham and moved into Cliveden View, a small house belonging to his brother, Percy. He was still in contact and corresponding with Hilda, and when she died of breast cancer in 1950, he was devastated and continued to write to her.

In what would turn out to be the final decade of his life, Stanley continued to paint prolifically. He often visited his elder brother Harold, who was living in Northern Ireland, producing portraits and landscapes while he was there. He also began work on a group of large paintings that, due to their immense size, were likely intended for his church house.

But, this project was interrupted when, in December 1958, he fell ill while working in his bedroom studio at Cliveden View. He was admitted to the Canadian War Memorial Hospital on the grounds of Cliveden and was diagnosed with cancer. Following a colostomy operation, he recuperated with the Vicar of Cookham before moving back to his childhood home, Fernlea, where he recovered well.

On the 4th of July 1959, he was awarded an honorary degree from Southampton University and, later that month, a knighthood from Buckingham Palace.

Sadly, remission was temporary, and after falling ill again, he returned to the Canadian War Memorial Hospital, dying peacefully on the 14th of December 1959. He was cremated and laid to rest with Hilda in Cookham Cemetery.

Only on the way to heaven have I eyes and can see.4

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this biography, please like and/or share it. Until next time…

Images:

Images on Beyond Bloomsbury are usually credited. I conduct thorough picture research, but please let me know if you believe a credit needs to be added or corrected. Thank you!

Sources and Recommended Reading:

Causey, Andrew, Stanley Spencer: Art as a Mirror of Himself (Lund Humphries, 2014)

Cottrell, Stephen, Christ in the Wilderness: Reflecting on the Paintings by Stanley Spencer (SPCK Publishing, 2012)

Hauser, Kitty, Stanley Spencer (Tate Publishing, 2001)

MacCarthy, Fiona, Stanley Spencer: An English Vision (Yale University Press, 1997)

Pople, Kenneth, Stanley Spencer: A Biography (Harper Collins, 1991)

Robinson, Duncan, Stanley Spencer (Phaidon Press, 1994)

Spencer, Stanley, Looking to Heaven. Vol I (Unicorn Publishing, 2016)

Stanley Spencer, Looking to Heaven. Vol I (Unicorn Publishing, 2016)

Kenneth Pople, Stanley Spencer: A Biography (Harper Collins, 1991) p. 55.

Pople, p. 209.

Pople, p. 496.

"Sadly, by now in his early forties, he was feeling dissatisfied and restless in his marriage and, as a celebrity, was receiving attention from other women."

- If one wishes for a perfect example of your sensitivity as a biographer, we could look far and long before finding a better one than this sentence.

Thank you for your concise biography of Spencer, and the paintings are tantalizing and I'll be seeking out more. I'd like to second the words of Laura McNeal.

The many fascinating artists' lives which you introduce to us only fortifies the purpose and importance of your endeavors. You are mining an incredibly rich milieu and we are your grateful beneficiaries.

This was a great and thorough introduction to the life and work of this artist.

His paintings are unusual in that many of them take a view from the rear, which makes them more arresting. My favorite is the Travoy picture. It had such an unusual orientation.

I also loved seeing the two self-portraits at the beginning and end of your essay. He looks younger than 23 in 1914 and older than 68 in 1959, understandable given his illness.