Vanessa Bell & Roger Fry: A New Direction

"As you know I care more for your opinion than anyone else’s."

Vanessa Bell, artist and founding member of the Bloomsbury Group - a circle of artists, writers, intellectuals and friends - met Roger Fry for the third time in January 1910, at Cambridge railway station. They had met briefly twice before, the first time at King’s College, Cambridge, and the second at a dinner party hosted by their mutual friend Desmond MacCarthy. This meeting, though, would alter the shape of her life and work, and Roger would become an intimate friend and key Bloomsberry.

It was again at Cambridge that I next met Roger… on that long platform waiting for the Monday morning train I said, ‘There’s Roger Fry - but I don’t think he remembers me.’1

Until 1910, Vanessa’s paintings had been traditional and representational - and influenced by artists such as Rex Whistler and John Singer Sargent. (Sadly, there are very few paintings to be seen from this period as much of her work was destroyed in an air raid in September 1940.)

But in 1910, Roger, who had discovered the Post-Impressionists - a name he conceived to describe European painters such as Cezanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Matisse collectively, organised the infamous exhibition, Manet and the Post-Impressionists, at the Grafton Galleries, London - which ran from November 1910 until January 1911.

It was, for most of the estimated 25,000 who attended, their first exposure to such works and the exhibition was heavily criticised by journalists, critics and the public. It had a marked impression on Vanessa, though.

The world of painting - how can one possibly describe the effect of that first Post-Impressionist exhibition on English painters at that time? … London knew little of Paris, incredibly little it seems now, and English painters were on the whole still under the Victorian cloud.2

Vanessa was not only greatly inspired by what she saw at the exhibition, but Roger also encouraged her to study the paintings of other artists and her work became colourful and abstract - with bright colours and bold designs. The exhibition also inspired her to paint what she wanted, rather than what was expected.

It was as if at last one might say things one had always felt instead of trying to say things that other people told one to feel. Freedom was given one to be oneself.3

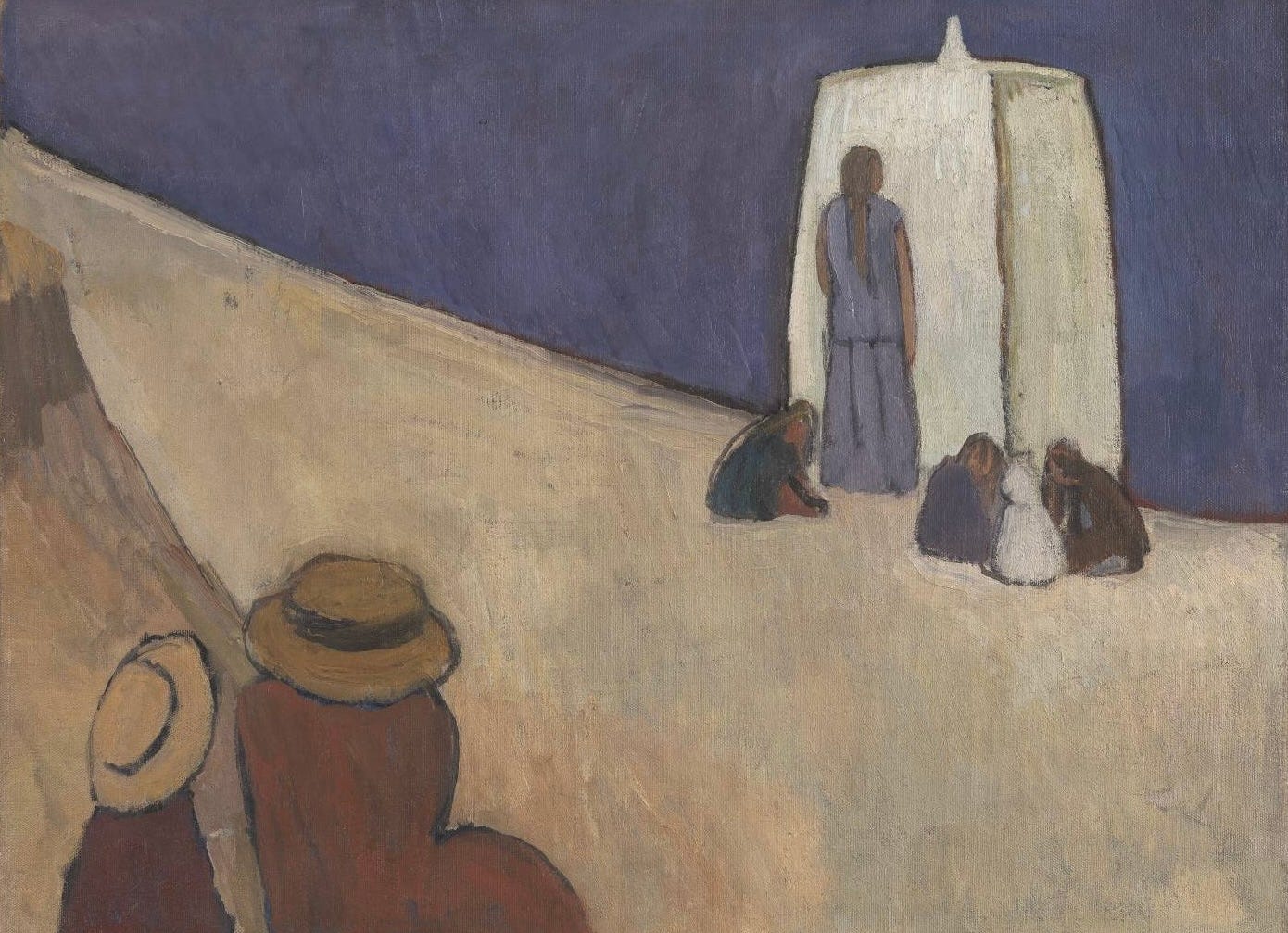

Studland Beach, painted in 1912, is an example of this freedom of expression. It is a simplified depiction of a landscape, and broad bands of colour are used to represent the sea, sky and beach. The intensity of the flat band of blue is one of the most distinctive aspects of the painting. According to Richard Shone in The Art of Bloomsbury, it was:

… one of the most radical works produced at that time in Britain and shows Bell more in step with some of her French and German contemporaries than with her fellow exhibitors in England.4

The painting also examines the principle of perception as two figures in the foreground (which, according to photographs from that time, are likely to be the young Julian Bell and his nurse Mabel Selwood) appear to be watching a group of figures in the top right, by a beach hut. We are only able to see the backs of these figures who, like ourselves, and the painting, face out to sea.

In the same year, Vanessa also painted two of her friends, Frederick and Jessie Etchells - also painting. Their faces are left blank without detail, and again, broad bands of loosely-painted colour are used to suggest a background.

A Conversation is another good example of Vanessa’s work at that time - with the simplified, flat forms of three women, large expanses of solid colour, abstract design, and form over content. She worked on the painting in two phases - in 1913 before the First World War, and again in 1916. It is a large piece, measuring 86.6 x 81cm, and depicts three women conversing in front of a curtained window, with what appears to be a flower garden in the background.

There is an energy and immediacy to the painting. The women’s conversation looks intense, their bodies are arranged closely together, their heads even closer as they lean in towards one another. It also lacks perspective, everything is to the front, bringing us close to the conversation, intimate almost - but yet unable to hear what is said. The two women on the right, one of them wrapped in a large fur coat, are listening eagerly to the pink-cheeked woman on the left - whose hand seems to be encouraging them to move even closer. In 1928, Virginia wrote to her sister about A Conversation.

I think you are a most remarkable painter. But I maintain you are into the bargain, a satirist, a conveyer of impressions about human life: a short story writer of great wit and able to bring off a situation in a way that rouses my envy.

In 1913 Vanessa joined with Roger and Duncan Grant to form the Omega Workshops - a design cooperative based in Bloomsbury that produced items for the home and gave artists a space to work together. Other avant-garde artists involved included Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Percy Wyndham Lewis, Nina Hamnett and Paul Nash. In founding the Omega, Roger had been inspired by Vanessa’s rejection of dark Victorian interiors in favour of light colour schemes, modern furniture and vibrant fabrics.

However, in 1916, two years after the start of the First World War, Vanessa and Duncan, a conscientious objector, moved from Bloomsbury to Charleston in Sussex and began working almost exclusively together.

In painting Nessa and Duncan have taken to working so entirely altogether and do not want me… I find it difficult to take a place on the outside of the circle instead of being, as I once was, rather central.

Letter from Roger to Clive Bell

The Omega also struggled financially and was forced to close in 1919 - by which time Roger was the only original artist working there. Vanessa and Roger’s friendship continued, though, and he continued to have an important influence on her work.

It seems to me really a very great honour to be written about seriously by you and that you should have thought it worth the trouble of trying to find out honestly what you thought about me… What really matters to me is that you take me seriously, for as you know I care more for your opinion than anyone else’s. Also your hints will be useful I hope. I think it’s true about my composition. Perhaps now I can try to think more of that.5

When Roger died unexpectedly in September 1934, Vanessa decorated his casket in a final tribute, and Virginia Woolf wrote in a biography published in 1940 that:

He had more knowledge and experience than the rest of us put together.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this biography, please like and/or share. And, as always, I would love to know your thoughts in the comments. If you wish, you can also Become a Member and/or read the suggested Beyond Bloomsbury posts below. Until next time…

Images:

Images on Beyond Bloomsbury are usually credited. I conduct thorough picture research, but please let me know if you believe a credit needs to be added or corrected. Thank you!

Sources and Recommended Reading:

Marler, Regina, ed. Selected Letters of Vanessa Bell. 1993.

Giachero, Lia, ed. Vanessa Bell: Sketches in Pen and Ink. 1997.

Shone, Richard. The Art of Bloomsbury. 1999.

Woolf, Virginia. Roger Fry: A Biography. 1940.

Giachero, Lia, ed. Vanessa Bell: Sketches in Pen and Ink. 1997. 120.

Ibid. 127.

Ibid. 130.

Shone, Richard. The Art of Bloomsbury. 1999. 74.

Marler, Regina, ed. Selected Letters of Vanessa Bell. 1993. 267-268.

A delightful read, loved the choice of paintings too.

A fascinating look at how Vanessa's style changed and was influenced by Fry. How sad that her early work was destroyed though; I hadn't realised that.