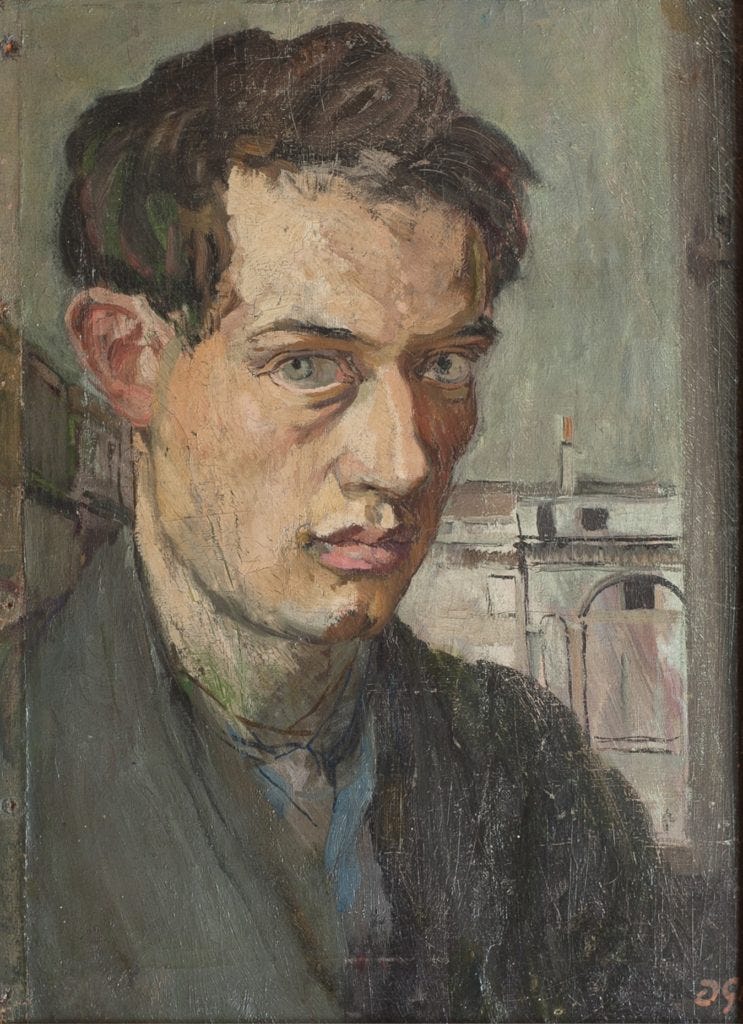

Duncan Grant: Life Before Bloomsbury

"It’s quite true, when he’s there all one can do is to be in love with him."

Duncan Grant was an innovative Post-Impressionist painter and designer with a prolific career that stretched over seven decades - from the Edwardian period to the 1970s. One of the leading artists of the early twentieth century, he was also one of the first British artists to paint in a wholly abstract style. He was a central figure in the legendary Bloomsbury Group, an association of artists, writers and intellectuals, and was described with fondness by writer Virginia Woolf:

[Duncan is]… a queer faun-like figure, hitching his clothes up, blinking his eyes, stumbling oddly over the long words in his sentences.1

Duncan was born Duncan James Corrowr Grant on 21st January 1885 at Doune - the ancestral home of Clan Grant of Rothiemurchus - three miles from Aviemore, Scotland.

He was an only child and his father Bartle Grant, an army major, met and married Duncan’s Australian-born mother, Ethel Isabel McNeil, at Gurdaspur in the Punjab state of India - where she was living with a cousin. Although the McNeil family descended from the lairds of Ayrshire, Ethel’s immediate ancestors had lived in Ireland before moving to Australia.

Bartle Grant was the youngest son of Sir John Peter and Lady Grant who had nine children (including Jane, mother of fellow Bloomsbury Lytton Strachey) and thirty-eight grandchildren. Sir John died two weeks before Duncan’s eighth birthday - whilst he and his mother were visiting him and Lady Grant at their home in Norwood, London. Though not particularly close to his grandfather, Duncan was devoted to his grandmother, a lady who loved art, music and literature, and also kept company with some of the important musicians and artists of the time.

As the son of a military officer, Duncan spent several years of his childhood, from the age of two, living in India and Burma where Major Grant was stationed. Although his father had some financial problems at that time, their domestic life was comfortable, with servants, drawing rooms and ‘modern’ conveniences. When Duncan wasn’t playing with the other army children, he was educated by a governess, Alice Bates, who encouraged his youthful interest in art and of whom he became very fond. Unaware of his father’s financial troubles, Duncan would later recall a significant moment when he was aged just six and dressed for a party in black satin breeches, ruff and a wig.

A strong feeling overcame me which I can only describe as an aristocratic feeling, suggested I suppose by my get up. But I distinctly remember the certain satisfaction of the feeling of power and direction with which I was filled. At that time of course, no sense of poverty had entered my life. We had many native servants. I had an English nurse. I was devoted to my mother and liked the company of the army officers, friends of my father. With this sense of security and background, it was easy to loll and dream of power, and to believe that to observe life was the way to live.2

Duncan returned to England when he was nine years old and enrolled at Hillbrow Preparatory, a small boarding school in Rugby, East Warwickshire managed by a Mr and Mrs T J Eden. The school taught just forty pupils, including his cousin James Strachey, son of his aunt Lady Jane Strachey, and younger brother of Lytton.

Duncan’s gift for art was encouraged at Hillbrow, not only by the school’s art master, but also by the headmaster’s wife who lent him a book of Edward Burne-Jones’ reproductions which had a huge influence on him.

For years I would ask God on my knees at prayers to allow me to become as good a painter as he is.3

Duncan won a number of art awards during his time there including Ruskin’s The Element of Drawing prize. He also excelled in music. Sadly, his lack of ability in other subjects was disheartening for his mother.

I cannot help feeling disappointed that he has not done better than he has at Hillbrow… at first they wrote so much about his ability and so forth. I remember Mr Eden saying to me once that Duncan had so many tastes, that he was afraid that he would never be good at any one thing. In his reports he always gets two excellent, one for music, the other for drawing.

Letter from Ethel Grant to Lady Strachey, 3rd June 1898

In the school holidays, Duncan would stay with his grandmother, who was then living in Chiswick, West London. He loved his time there as Lady Grant talked to him about her life, her travels in Italy, her love of art and her creative friends.

On turning fourteen, Duncan left Hillbrow to complete his formal education at St Paul's, a day school in West Kensington that welcomed the children of army parents. Although he again excelled in art, winning seven prizes in the subject, he was also known to play the fool in many of his other classes and, with encouragement from Lady Strachey, his parents decided that he should look beyond the constraints of traditional schooling.

I am sorry to lose Duncan both from my form and my house, and wish even apart from that, that he would be a schoolboy a little longer. I have always felt that I only had him by two strands of a rope… He is such a pathetically loveable creature, I cannot bear the idea of his not doing the right thing.

Robert Cholmely, Housemaster

In 1902, aged seventeen, Duncan enrolled at the Westminster School of Art and moved into the Strachey’s eight-storey home in North Kensington. Five years older than Duncan, Lytton was at that time studying at Trinity College, Cambridge, having previously studied at University College in Liverpool. But, with ten other young people in residence, including James, the house was still vibrant and chaotic and Duncan is said to have enjoyed his time there.

Duncan is very cheerful and I am sure he likes his work; he is a very nice boy indeed and most pleasant in the house. He and Jem [James] seem to get on very well too and do have similar tastes.

Letter from Lady Strachey to Bartle Grant, 11th February 1902

Like Lady Grant and Alice Bates, the Stracheys were also passionate about the arts and would often entertain artists in their home, including Roger Fry and French artist Simon Bussy - whom they had met during a trip to visit their daughter Dorothy when she was studying for a doctorate in Paris. Bussy, a friend of Henri Matisse, moved to England and into a studio nearby where he started teaching to supplement his income.

His lessons remain with me as the best I have ever received. He was the most just of masters but at the same time the most severe.

Duncan Grant’s speech notes for a Simon Bussy exhibition in the 1940s

In the winter of 1904, Duncan travelled to Florence with his mother. Every day he would visit the Uffizi, a gallery in the historic centre of the city, and was mesmerised by the early renaissance paintings of Piero della Francesca and Massacio that were exhibited there.

When they returned to London in early 1905, Duncan visited the National Gallery to view Piero’s The Nativity, a painting that depicts the birth of Jesus and is one of the artist’s last surviving paintings. And, on advisement from Simon Bussy, he copied aspects of the painting including Mary and Joseph, and the angel musicians.

It was also in 1905 that Duncan travelled to Cambridge to visit Lytton at Trinity College. There he met members of The Apostles and was encouraged by Lytton to read G.E. Moore’s Principia Ethica. Moore was an important figure in philosophy at the beginning of the twentieth century and became an elected fellow at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1898, where he remained until 1904. In 1903 he published Principia Ethica, a major ethical work in which he argued for the primacy of personal relationships, love, knowledge and aesthetic experience above all else.

Duncan had also become aware of Lytton’s increasing attraction towards him. However, it wasn’t until the summer of 1905, whilst the Stracheys were holidaying at Great Oakley Hall, near Kettering, that Duncan accepted him.

Incredible, quite - yet so it’s happened… Oh dear, dear, dear, how wild, how violent, and how supreme are the things of this earth! - I am cloudy, I fear almost sentimental. But I’ll write again. Oh yes, it’s Duncan. He’s no longer here, though; he went yesterday to France. Fortunate, perhaps, for my dissertation.

Letter from Lytton Strachey to John Maynard Keynes

In 1906, now aged twenty-one, and living in a tiny studio at Upper Baker Street, Duncan accompanied Lytton to a meeting of the Friday Club - a group founded by Vanessa Stephen for the discussion and exhibition of art. There he was introduced to like-minded people who would become his lifelong friends and founding members of the Bloomsbury Group.

It’s quite true, when he’s there all one can do is to be in love with him.

Letter from Lytton Strachey to John Maynard Keynes, 17th November 1905

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this biography, please like and/or share it. If you wish, you can also Become a Member. Until next time…

Images:

Images on Beyond Bloomsbury are usually credited. I conduct thorough picture research, but please let me know if you believe a credit needs to be added or corrected. Thank you!

Sources and Recommended Reading:

Bell, Quentin. Bloomsbury Recalled. 1995.

ed. Rosner, Victoria. The Cambridge Companion to The Bloomsbury Group. 2014.

ed. Ryan, Derek & Ross, Stephen. The Handbook to The Bloomsbury Group. 2018.

Spalding, Frances. Duncan Grant: A Biography. 1998.

Spalding, Frances. The Bloomsbury Group. 2017.

Watney, Simon. The Art of Duncan Grant. 1999.

Woolf, Virginia. The Complete Collection. 2017.

Spalding, Frances. Duncan Grant: A Biography. 1998. 10.

Ibid. 13.

Fabulous research and exquisitely written. A pure joy to read. Thank you so much.

A very interesting, and illuminating article! Thank you.